Additional Information About The Book:

Reading History Sideways Overview

In the recent book, Reading History Sideways: The Fallacy and Enduring Impact of the Developmental Paradigm on Family Life, Arland Thornton describes reading history sideways as an approach to history that was commonly used by scholars in the past, whereby cross-sectional data were used to describe history rather than just to make static comparisons. Although this method has been often used, Thornton points out numerous flaws in its design and reminds readers that the method has itself been discredited. However, he argues that in order to understand the history of family and demographic studies, an understanding of reading history sideways is essential. The method is described below.

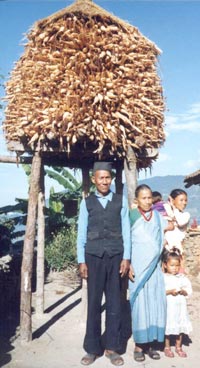

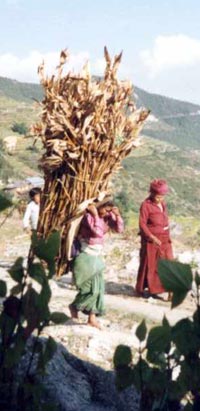

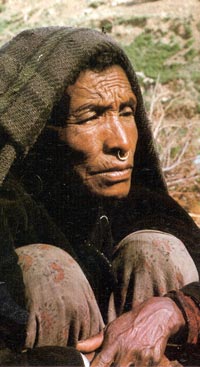

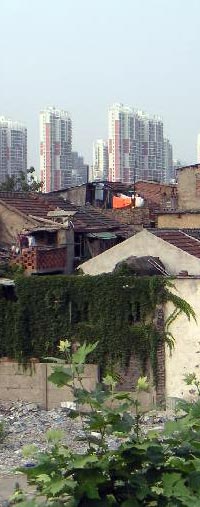

Reading history sideways is an approach to history that, instead of following a particular society or population across time, compares various societies at the same time. This method takes advantage of the assumption of the developmental paradigm that at any single point in time, all societies can be pegged at various stages along the same development continuum. It assumes that the previous conditions of life of a presumably more advanced society can be proxied by the life situations of a contemporary society believed to be at an earlier stage of development. That is, the contemporary society perceived as less developed is used as a proxy for circumstances at an earlier historical period of the society that is perceived as more advanced. A belief in this approach makes it possible to portray societal change using information from populations observed at the same time but in different geographical locations.

Scholars have read history sideways for several centuries to construct histories of virtually every dimension of human life. They were especially fascinated with the variety of religious, familial, economic, and political institutions around the world, and they energetically compared these social institutions, crafting the data that they obtained into complex accounts of social change across developmental stages of history. They produced numerous—and often lengthy—treatises of the history of marriage, women, religion, economics, and politics. Although these scholars used similar methods, they created different versions of historical trajectories, resulting in extensive disagreements and debates about the way that history had unfolded.

Reading history sideways, of course, required a system for ordering contemporary societies along the trajectory of development. We should not be surprised that ethnocentrism led the people of northwest Europe to believe that they were at the pinnacle of development. They were also aware of Western military and political ascendancy, and understood well which countries had the most wealth, guns, and power. They also knew that northwest Europe had experienced changes in the sciences, education, technology, and economics, and used these as criteria of development.

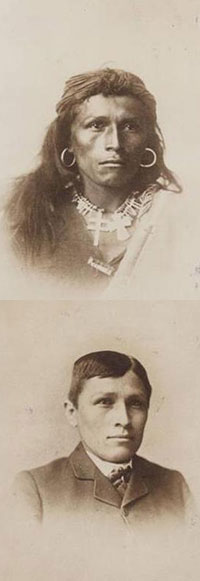

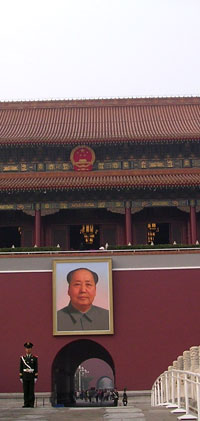

Societies that were most different from Europe were used to represent what scholars believed to be the least developed end of the continuum; the rest of the world’s populations were arrayed between the least and the most advanced societies. Edward Tylor, an important English scholar of the era, suggested that “few would dispute that the following races are arranged rightly in order of culture: Australian (aborigines), Tahitian, Aztec, Chinese, Italian”; the English ultimately were the highest. Of course there were many variants on Tylor’s developmental ordering of contemporary societies, but the general approach was the same.

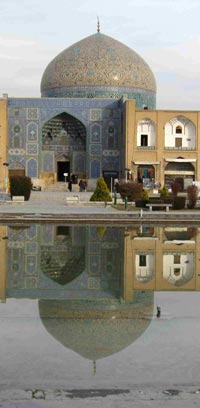

These scholars believed that they could describe societal change by reading history sideways on a trip around the world. Instead of reading the history of actual societies from the past to the present, they believed they could read the history of the European past in the non-European present. Furthermore, by looking at the trajectory implied by this developmental geography, they believed they could predict the future of Asia and Africa.

Thornton’s book, Reading History Sideways, provides additional information about the method, its conceptual underpinnings, and the results scholars produced using it. The book also provides a critique of the method and its underlying assumptions and describes the many misunderstandings of family history produced by reading history sideways.